|

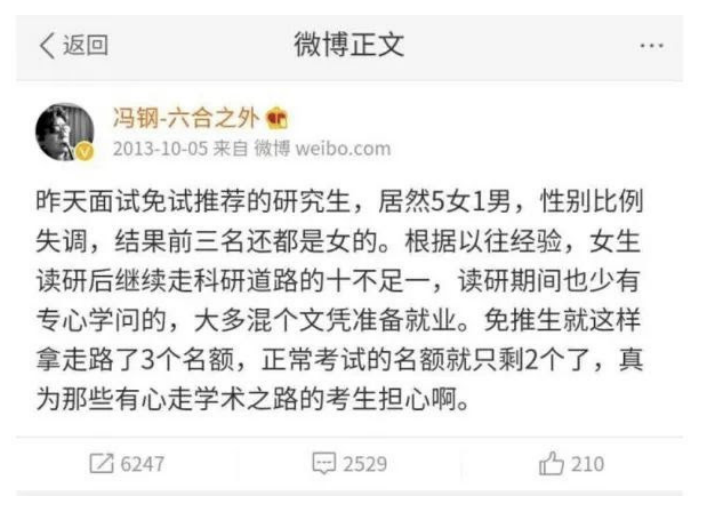

Note: This article was first written in Chinese on October 24, 2017 and translated into English in 2018. A post written on Weibo (a Chinese microblogging website) in 2013 by Feng Gang, a sociology professor from Zhejiang University, has recently resurfaced and led to a heated discussion online. My friend and colleague suggested that as a leading blog in China that aims at promoting gender equality, Ms-Muses should publish a response. Therefore, I take the initiative to write this article. I would like to start by sharing my experience growing up from a little girl (in a patriarchal society) to a university professor (with research interests in gender relations and social inequality). I will also provide some relevant research findings later in this article.

Ever since I was little, my mom, along with my friends’ parents, had always told us, “Women should not work too hard. It is far more important for girls to marry well than anything else.” Yet, under such childhood environments, I became a feminist.

Although I was always at the top of my class from elementary school to junior high school, all my teachers, even my mom included, kept reminding me that getting good grades in my early education did not necessarily mean that I would still get good grades later on. In contrast, although my male classmates were not as hardworking, and their grades certainly were not as good, they still often received praises from teachers and parents saying, “You are so smart; you will have really good grades if you just put in a little bit more effort.” To this day, I still remember one math teacher in my elementary school, who had a respectable reputation in the district, commented in my homework: “Yue’s academic performance is good, but she is not smart. She’ll have to work hard to make up for a lack of intelligence.” In high school, I got into the “Olympic Class” in which students were trained for international science Olympiads. We had to learn three years’ worth of math, physics, biology, and chemistry in Grade 10. I had a hard time catching up to this kind of pace and my grades began to drop, which seemingly confirmed the conventional expectation that “girls would eventually fall behind boys in school.” My math teacher even arranged a one-to-one meeting with me, suggesting that I should drop out of the “Olympic Class.” Looking back, I am actually very proud of my younger self. Despite being a powerless little girl, I was brave and determined enough to tell the powerful male teacher, “No, I am not quitting. I want to stay.” (To some degree, I also feel grateful that he respected my decision at that time.) In order to stay in the class, I worked extra hard throughout the rest of my high school years. I wrote down every question that teachers discussed in class, and then went over it again on my own. The next day, I asked my friends to explain to me the harder questions that I did not understand. I scored only 46% in math exams for a long time, but in my last year of high school, my mark went up to 92% for the first time. At the time I felt very satisfied with my progress. However, my math teacher said to me privately, “You did well this time…(pause)…but it was mainly because the exam was easier”. In fact, up until the end of high school, I maintained my math average at 92%. How can I still vividly remember things that happened over ten years ago? It is because these kinds of encounters have made me realize how bumpy and difficult the road to success can be for women. In addition, in every mock exam, nine out of the top ten students in my cohort were female. Yet, our Chinese teacher made a comment in front of the whole class, “There is only one male student out of all top ten students in sciences; this is very abnormal. In an older cohort, there was only one female student among the top ten students; that’s the way it should be.” Even as a high school student, I already wanted to start a revolution in class. Why was it considered as “abnormal” for female students to achieve academic excellence? Why was my performance in math attributed only to hard work, but not to my intellectual ability? Why did the teacher think it was only because “the exam was easier” when my math grades significantly improved? Looking back, my reactions were quite immature at the time. I used my rebellious adolescent way to show my resentment. For example, I would sleep through my Chinese class, eat my breakfast during early morning classes, and remain seated while my teacher demanded me to stand still for a certain period of time. During my senior year of high school, I remained among the top students in my cohort. Eventually, I went on to a prestigious university in Beijing. Strikingly, I encountered a male professor in college who expressed his belief in class that “women do not belong in academia.” I found it extremely ridiculous that he could make such remark when he had so many outstanding female colleagues and had a daughter as well. In graduate school, there were many incidents where my friends, who worked in male-dominated fields, told me that “male graduate students in the department always get together and gossip about the female professors who all seem to be beautiful blonde women.” All these experiences sparked my interest in gender studies. From undergrad, to grad school, and PhD, I met numerous inspiring and accomplished female role models whom I looked up to. Their hard work, rigorous research, and passionate curiosity, along with their genuine desire to provide support and guidance for students, aspired me to push forward. As I got to know more about gender research, I realized that girls have been outperforming boys for a long time in the classroom. According to U.S. historical evidence, girls had long surpassed boys academically in secondary school. One reason why women lagged behind men in attaining tertiary education was that most universities did not accept female students (DiPrete & Buchmann 2013). It was not until the inception of the Seven Sisters (colleges) that most universities began accepting female applicants. Currently, in the United States, about 60% of the bachelor’s and master’s degrees and 50% of the doctoral degrees are awarded to women. Even in China, women have surpassed men in college enrollment ever since 2009 (Yeung 2013). Nevertheless, even today, we still see comments such as “less than 10% of female graduate students take academia as their career path after graduation.” Professor Feng Gang should ask himself: Is it really because women are less competent? How come we never question whether the academia is really female-friendly? Women still take on a greater share of the housework and childcare burden. Balancing familial and domestic duties with work is something that most female PhDs and professors have to consider and worry about. Claudia Goldin (2004) found that by their mid-30s to mid-40s, college graduate men managed to achieve career and family about two times as often as women. A lot of times, women are put into the predicament to choose between their career and family, but this is seldom a problem that men have to face. Even if women work harder to balance both work and family, they may still be unfairly evaluated as less ideal workers who will eventually drop out of the workforce for familial duties. Shelley J. Correll and her colleagues (2007) conducted an audit study in which participants evaluated application materials for a pair of equally qualified female job candidates who differed on parental status. The results showed that mothers were perceived as less competent and less committed to their work and were even recommended for a lower starting salary. This is my story. I believe every woman has their own story to share, a story that “nevertheless, she persisted.” Hillary Clinton once said, “Although we weren’t able to shatter that highest, hardest glass ceiling this time, thanks to you, it’s got about 18 million cracks in it and the light is shining through like never before, filling us all with the hope and the sure knowledge that the path will be a little easier next time.” It is numerous women’s effort and persistence that enable positive change, inspire action, and move communities forward. In short, every country should advocate for feminism and gender equality, not because women are men’s mothers, wives or daughters, but because “women’s rights are human rights.” The opportunities, successes, and accomplishments that women enjoy today are attributable to the perseverance and hard work of many generations of women. Throughout their lives, every woman faces gender discrimination both blatantly and covertly. Here, I would like to pay my tribute to all the women who have persisted, regardless of how many times the society has made them doubt themselves. I also want to ask everyone to stop judging girls and women based on stereotypes, because bias is what holds many women back. Author Note: Here is the link to the original article in Chinese: "一位‘坚持走科研道路’女学者的自白." The author, Yue Qian, would like to thank Christine Yang for her assistance with translations from Chinese to English.

1 Comment

|

Yue QianAssociate Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|