|

Note: This article was first written in Chinese on October 27, 2020 and translated into English in 2022. I did a lot of immature things in graduate school. Now looking back on it, I would like to share the lessons regarding how to best work with professors. These reflections are all based on my personal experiences and those of my friends. Please feel free to share your thoughts as well. 1. Consulting with advisorIf you already have a scholarship or hold a Research/Teaching Assistant position but you want to look for other “side jobs” unrelated to your research, it is best to discuss it with your advisor first. I recommend this because it is not easy for students to manage time with too much on their plate. Biting off more than you can chew tends to delay your graduation or current research. By talking to your advisor about the things you want to pursue, they can offer you advice on the best course of action to take. To give an example, when I was pursuing my PhD, a professor in the business school was looking for assistance with data analysis. I was quite confident in my abilities to do this type of work and applied for the position without consulting with my advisor. He eventually found out my side job because the business school required my department head’s signature to process a payment and my advisor just so happened to be the department head in charge of approving my pay. My only choice after that was to explain myself to him. My advisor asked me whether this job was temporary or long-term, and he was understanding and did approve my salary. I was fortunate that the RA job only required one-time support on data analysis, so I was able to return my focus to research without falling too behind. From this, I learned that I had been too ambitious with my goals. Next time, if I were to come across any potential “opportunities,” I should first discuss them with my advisor and then make a decision based on my academic workload and future career plans. 2. Writing down your research ideaIt is great to have research ideas, but we shouldn’t constantly change our minds. When advisors offer constructive criticism for a research proposal, we should take time to think about how we can incorporate their suggestions to improve the research design as opposed to changing our research question the moment a flaw is pointed out. If it is possible to improve the proposal, then how should that be done? What we should avoid doing is changing our research topic at the first sight of criticism. When I was choosing my dissertation topic, I had meetings with my advisor every week and I reported my progress to him. We soon fell into a cycle where I would propose my idea, he would point out some questions for me to think about, and I would come back the following week with a brand new idea. When this had gone on long enough, my advisor said something along the lines of: “You come to see me each week and propose a research topic. I tell you what challenges you may face if you decide to pursue this topic. I raise questions about your proposed topic, but they aren’t meant to discourage you from moving forward with the topic because it’s no good; rather, I intend to help you improve your research idea. But if every time I raise questions, you change to an entirely new topic; then there is no point in meeting every week because it is a waste of our time. I suggest you write down your ideas and address the following points in a few paragraphs: What is my research question? Why is this topic worth investigating? What data may be appropriate? What challenges may I face? Writing these down can help you organize your thoughts.” After hearing his words, I felt quite ashamed. I had been changing my dissertation topic so frequently that even though we met often to discuss my work, I was making no progress on identifying a good research question. After our conversation on that day, I organized my research idea into some paragraphs and followed my advisor’s advice to sort out my idea. I soon found my dissertation topic. 3. Preparing questions before meetingsBefore meeting with your advisor, prepare questions. When I was in grad school, I set up weekly meetings with my advisor, to keep myself accountable and prevent myself from procrastinating. One time, when I walked into my advisor's office and he asked me, “What would you like to discuss this week?” I then realized that I had nothing new to discuss with him. He told me with a smile, “Next time if you have nothing to discuss with me, just tell my secretary or send me an email to cancel our meeting. Don’t feel bad; I have plenty of other things to do.” Through that experience, I have learned that students need to have a proactive attitude when meeting with their advisor. In particular, if students meet with their advisor to discuss their own research, they cannot assume that their advisor knows what progress they have made because advisors have no such obligations. To have productive discussions, students need to regularly keep track of the problems they run into and go into meetings with questions prepared beforehand. 4. Informing professors in advanceProfessors have busy schedules so you should inform them in advance if you need help. A reliable friend of mine told me that she was once immature when interacting with her advisor. Her advisor responded very quickly to emails and students’ needs. However, one time she contacted her advisor so last minute, so her advisor made it clear to her, “I know I reply quickly to emails but not that quickly. Please tell me ahead of time if you need my support.” A friend of mine who works at a university in China told me stories of students who would frantically ask professors for signatures or even recommendation letters on a weekend and require them by Monday. Students should not treat their professors as 24/7 customer service workers. Professors do not owe students all their time, so please be respectful and considerate when making requests. There are some things to be mindful of if you wish to ask for recommendation letters. Outside of seeking permission, I have colleagues who require their students to share all their related documents at least one month before the deadline. Overall, when it comes to writing recommendation letters, every professor has different requirements and preferences. Therefore, for students, the best course of action is to do your part ahead of time and communicate with professors sooner rather than later. To give an example, when I was on the job market, I was applying for many jobs, so I sorted those jobs by the due date for recommendation letters. For schools with October due dates, I would send my professors a list of schools in mid-September and include their associated links for submissions of recommendation letters. If a deadline was around the corner but in the application system, I had not yet seen recommendation letters submitted, I would send a follow-up email to remind the professor(s). When I was a student, I was extremely grateful for the support that my professors provided to me. To thank them, I figured the best thing I could do was to make it easier for them to support me. 5. Taking feedback seriouslyWhen you receive revision suggestions from your advisor, you should take time to reflect and make corresponding changes. Furthermore, you should strive to not make the same mistakes.

A friend once told me that when she was supervising MA students’ theses, she would make many annotated suggestions on their drafts. However, when students turned in the next version of their drafts, there were no tracked changes, so she did not know what changes were made to the papers. When she spent time comparing the previous version to the current one, she found out that the issues she had raised were still present. My friend said, “I had no idea if the student didn’t make the changes because they disagreed with my comments or if they agreed but just didn’t know how to address them. Or could it be that they were simply unwilling to take any suggestions at all?” In graduate school, when I was quite doubtful of my academic career, one professor said to me, “I truly believe you have potential because you take criticisms well and you know how to improve your work based on the criticisms.” She found that some students were unwilling to listen to critiques, and others listened but couldn’t seem to address the critiques to improve their paper. Thus, taking criticism well and knowing how to revise our paper based on the criticism are extremely valuable research skills. These are all the examples I could think of from the top of my head. If you have other opinions or thoughts, please feel free to share them. Last, I would like to say that if you (especially those still in school) feel that you have done any of the immature things mentioned in the article, don’t feel as if it is the end of the world. None of this is meant to say if these mistakes are made, then our relationship with our advisor is ruined. All professors want the best for their students. If we can learn from these experiences, reflect, improve, and grow, then that is what makes the biggest difference. Author Note: Here is the link to the original article in Chinese: "和教授共事,哪些雷区不要踩?." The author, Yue Qian, would like to thank Evalina Liu for her assistance with translations from Chinese to English.

31 Comments

Note: This article was first written in Chinese on November 13, 2020 and translated into English in 2022. This week, a collaborator and I completed a minor “revise & resubmit” in two days; in the last two weeks, another collaborator and I wrote in sprints and finished a high-quality literature review of over 5,000 words. While working on these research projects, I felt sincerely grateful for all my awesome collaborators. Therefore, I couldn't help but write an article to share what I’ve learned from them. 1. Be reliableI've tried writing sprints this year with several collaborators, and it's pretty cool! Generally speaking, after I finish a draft, I send it to my collaborator, and my collaborator will edit it as soon as possible, and send it back to me, and we repeat the process a couple of times. I found that through this collaborative approach, we were able to complete both the first draft and the final polished draft within a short time. Sprint writing has a lot of benefits. For example, when working on a project, if my collaborators and I put it on hold for a while, it always takes a while to recall what we did last time and then plan what to do next. However, sprint writing is like running a relay in which collaborators pass the baton to each other and let the ideas flow logically. As a result, we not only efficiently write up an article but also substantially improve the article with multiple rounds of back-and-forth revisions. If we have to take time off to deal with personal circumstances, such as recovering from sickness or taking care of children, my collaborators and I usually communicate in advance to make sure that both parties are on the same page. For example, they may tell me “I can only make changes up till this part today. I will leave the rest to you, and come back tomorrow to follow up on your edits.” In another instance, I was not productive in a particular week, so my collaborator did her part first and sent it over. The next week, she had other things to do, so she didn’t work on our project. Instead, I revised what she wrote, added the parts I was responsible for writing, and then sent it back to her. Later, she said to me, "How amazing it is to have a coauthor who you can really depend on!! Thanks for pushing the paper forward." Of course, this kind of dependence is not one person's unilateral effort, but everyone's concerted endeavors can develop a synergy. Sometimes I'm afraid that I would procrastinate and delay things, so I set a deadline for myself. For example, instead of saying "I'll reply to you as soon as possible," I would say, "I'll look at it and reply before Wednesday." I do so because I find that saying "as soon as possible" doesn’t mean the project is on my to-do list and it may end up being put on hold for various reasons. However, if I promise myself a deadline and keep myself accountable by telling my collaborators about my plans, I can make sure that I'm responsible for the project. I also have collaborators who clearly explain their arrangements and plans. For instance, they let me know that they are preoccupied, so they may not be able to participate in a project, and they will join if other opportunities arise in the future. In short, reliable collaborators inspire us to become more trustworthy and committed members of a research team 😁 2. Be intellectually stimulatingI often ask questions to spark discussions with collaborators, and I am very grateful for their constructive suggestions. Collaboration, in many cases, is being able to discuss with someone when you get stuck or feel uncertain about something. After all, two heads are better than one. In emails and Word documents, I raise questions if I am unsure about certain things. I appreciate how genuine and sincere my collaborators are in responding to my questions. They share their ideas or potential solutions, and they are usually quick and thoughtful. I always feel more motivated and driven after reading comments and suggestions from my collaborators. Their replies also help me think more deeply to gain a better understanding of our projects. I often feel cheerful because I have acquired new skills from these projects. In collaborative research projects, intellectually challenging and stimulating dialogues are one of the most enjoyable aspects of collaboration. It is not uncommon that my collaborators disagree with me and challenge me. For instance, they point out that:

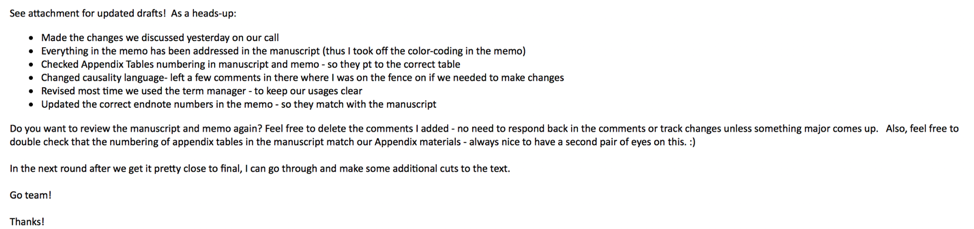

Here is what I feel most grateful for: when collaborators express their disagreement, they usually come up with a plan that they think is feasible, and then we would consider it and discuss the next steps together. This kind of back-and-forth questioning and discussion makes research better. 3. Be organizedMy collaborators are all very well-organized persons, and I have learned a lot from them. In email exchanges, many of my collaborators give me an outline of what they have done and also tell me what needs to be done next. They are my role models and motivate me to be more organized. Once, a collaborator sent me a structured email that I still remember to this day (see the image below). When I saw it, I thought, "I need to learn from her!" She laid out very concisely what she did based on our discussion, then pointed out what I needed to do and what I should pay attention to, and also specified what we may need to do together in the next stage. Last, she ended the email with affirmation - "Go, team!" and "Thanks!". After I read the email, I was influenced by her optimism and positive energy. 4. Establishing good authorship practicesCo-first authorship has become increasingly popular in academia, but how to order author names amongst those who contribute equally is a rather awkward topic. While the default practice is normally to list co-first authors alphabetically by last name, it might come off as a little bit unfair to those with last names late in the alphabet. Academics with last names further back in the alphabetical order may find it difficult to voice out their potential concerns about always being the last person on the author list. The situation can be even trickier if there are differences in rank or seniority between the collaborators. If an author with a later alphabet surname is of lower rank or seniority, the author may not know how to voice out their concern without being viewed as aggressive; by contrast, if it is the party of higher rank or seniority who proposes to change the order of names, it might come across as abusing their power. In these situations, it may be a good idea if the party with the first alphabetical surname takes the initiative to propose some solutions that they could accept.

One time, a collaborator took the initiative to tell me, “Yue, this time your name should be listed before mine”. Although his last name technically goes before mine, he said that his name was listed first last time when we worked together, so this time mine should be listed first. I was really moved by his consideration and thoughtfulness 😭 I have seen other mutually agreed-upon practices. If two or more people are long-term collaborators and are co-first authors on multiple papers, it may be reasonable to rotate the order of the names. For example, this time, A is listed first, and next time, B is listed first, even when all the articles indicate that the authors contribute equally. I also know of collaborators who flip a coin to decide whose name appears first on the paper. Many long-term collaborators put themselves in each other’s shoes, and treat each other as partners and friends. We strive to be fair, friendly, and ethical in handling situations that arise in collaboration. Well, that's it for today's sharing. Please feel free to leave a comment for discussion😊 I wish you all can connect with trustworthy and reliable collaborators! Author Note: Here is the link to the original article in Chinese: "我从我的合作者身上学到的美好品质." The author, Yue Qian, would like to thank Ally Cheng for her assistance with translations from Chinese to English. Note: This article was first written in Chinese on December 9, 2022 and translated into English in 2023. A while ago, I saw a conversation between alumni and a faculty member from the Ohio State University on Twitter about creating CV (Curriculum Vitae, resume in academia). Their conversation, coupled with my observations of academic hiring processes and my experience in helping students revise their CVs, made me realize that the "common CV mistakes to avoid" were not knowledge everyone knew. So today, I'd like to share some insights. Before sharing, I need to clarify that my summary of the "common CV mistakes to avoid" is based on my own understanding from my experience. I cannot guarantee the universality of these suggestions. Moreover, my advice may be more applicable to the culture of North American academia, and I have limited knowledge of its applicability to Europe, Asia, or other regions. Readers with experience outside North American academia are welcome to share your thoughts. So, how important is CV?Jobs, grants, awards, and many other opportunities in academia often require submitting a CV as the first piece of material. I attended a workshop on "academic job market" in graduate school. The professor leading this workshop said that among all the materials submitted for job applications, CV might be the only (or one of the only two materials, with cover letter also being important) material that would be reviewed by almost every colleague in the hiring department. In addition, screening CVs is often the first step in academic hiring. If a CV is deemed "passable," the hiring committee may continue to review other materials. Moreover, academics' professional trajectories are often made public. When we search for scholars online, their websites usually include their CVs. It can be said that CV is the main venue for people to understand a scholar’s past experiences and recent updates in academia. The basicsIn graduate school, I was advised to find some scholars whom I admired and see how they designed their CVs. Clear layout, well-organized content, and no typos are basic requirements, so I won't elaborate on that here. A CV includes some basic sections, such as education, employment, publications, grants, awards, invited talks, conference presentations, teaching, and service. Generally, education and work experience are essential background information and are listed first. Then, among other content, publications are a crucial part of academia (especially in research-intensive universities). As a result, people often list their peer-reviewed publications immediately after the "employment" section. However, some people may highlight their most impressive achievements on the first page. For example, the ability to secure external grants is highly valued in academia. Thus, if someone has received numerous large grants, they may choose to list grants before publications. Similarly, if someone has won many prestigious awards, listing awards earlier in the CV can leave a strong impression. In short, when arranging CV content, consider conventions and also think about the most valued skills and achievements for the opportunity you're seeking. What are your core competencies among all the selection criteria? Once you think through this question, you can organize your CV accordingly. In today's article, I just want to offer one major piece of advice for creating a CV: Don't inflate your CV! This advice can be expanded upon in several ways. 1. For academic publications at different stages, it is essential to distinguish them clearly, preferably using separate sections.This suggestion is actually the same as the one in the screenshot above: Don't list your manuscripts under review with your publications on your CV. Generally, academic publications have several main stages:

Generally, item (a) will be a separate section as it is confirmed and one of the most crucial parts of a CV. Whether to include (b), (c), and (d) on your CV depends on the individual, career stage, or the reason for submitting the CV. Typically, when being on the job market, people list (b), (c), and (d) as we want to signal to future employers, "I have set up my publishing pipeline!" If you decide to list (b), (c), and (d), be sure to separate them from (a); otherwise, it may seem unprofessional or even an attempt to inflate your CV. For item (d), some may wonder if listing more is better. That's not necessarily the case. I remember someone telling me not to list too many works in progress. Especially if you don't have many publications but list a lot of work in progress, people might question, "Does this person lack the ability to carry a project from beginning to end and produce published papers?" After all, what ultimately matters is not how many ongoing projects we have but how many papers we have successfully published. When we list work in progress, we could briefly describe the completion level (e.g., draft available upon request) to give people a more concrete impression of the project's potential. Also, don't exaggerate the amount of work in progress. If you're not actively progressing a project or it has been stagnant for a long time, there seems no need to list it. I've heard of people emailing their co-authors (first author) to ask if they plan to continue the project and if so, what the next steps are; if not, they plan to remove the project from their CV's work in progress section. 2. For different types of academic publications, it is essential to distinguish them clearly, preferably using separate sections.Whether we like it or not, different academic publications carry different weights. For example, peer-reviewed books and journal articles are generally well-recognized achievements in academia and carry the most weight when we are looking for a job or going up for tenure/promotion. Book chapters or book reviews have relatively less weight. Non-peer-reviewed publications or non-academic publications, such as writing short articles for magazines or newspapers (like the one I'm writing now, lol), are considered public engagement and are only supplementary outputs. When creating a CV, be sure to separate these non-academic publications from the "weighty" conventional academic achievements. If we list these items together, others may find us unprofessional, or worse, think we are deliberately inflating our CV. I've heard a story about a PhD candidate at a prestigious university. At first glance of the CV, that person seemed very productive, with many single-authored articles as an ABD (All But Dissertation) student. Upon closer examination, only one article was peer-reviewed, while the others were non-academic short pieces written for organizations or media. A friend lamented, "I can't understand why that person did this. Didn't anyone in their department or their advisor review their CV or point out this issue to that person?" People generally skim through CVs quickly, so when creating our CV, we should put ourselves in the readers' shoes and think about how to present our past achievements and future plans in the clearest and least misleading way possible. When preparing our CV, we should consider whether others can easily find the information they need. Since one of the main functions of a CV is to showcase our academic publications, this section should be listed separately instead of being mixed with unpublished or non-academic works. 3. Avoid mentioning the same information in multiple places in your CV.I can’t remember where I saw this piece of advice. As for this suggestion, I'm still exploring: When would it be seen as a negative signal? When is it appropriate to not only place important information in the corresponding section but also directly link it with other content? For example, if someone's book or paper has won a prestigious award, they might list this information directly below the book or paper, but they will also include the award again in a separate Honors and Awards section. Most people don't seem to find this practice problematic. However, I think the reasoning behind this suggestion is similar to what I shared earlier: If the same information occupies multiple lines in different places in a CV, it can easily give the impression of inflating one's achievements. Lastly, I want to share a positive insight. Many of my friends, when facing bottlenecks or feeling they have not made progress, update their CVs and then realize they have accomplished so much without even recognizing it! I hope everyone has an impressive CV, and behind it is a joyful journey of learning and working. Author Note:

Here is the link to the original article in Chinese: "这些学术简历大忌,你中了吗?" Note: This article was first written in Chinese on June 5, 2019 and translated into English in 2022. I have always wanted to write an article on collaboration. I often joke with my friends in academia that finding a good collaborator is not in any way easier than finding a life partner. If we are lucky enough to meet good collaborators, we should never let them go. Last month when I was attending a conference in the US, a fellow in academia pointed out to me, “you seem to collaborate a lot in your papers”. Indeed, I love collaborating with others. In “how to manage your time, emotion, and research progress as pre-tenure faculty members?,” I mentioned that writing sole-authored papers was lonely (at least this is how I felt). I had no one to talk to for advice with regards to the details of the project. No one could motivate or encourage me to actively continue my research. On the contrary, with a collaborator, we can keep each other accountable and discuss any possible questions, which in turn makes us feel much less isolated. I have grown a lot from collaborating with other people and learned to become a better researcher and better person in general. l I would love to share my experience with all of you. Specifically, I am highlighting peer collaboration in my examples below. On the flip side, if it were a collaboration between a junior researcher and a more experienced, senior scholar, it would look more like a mentor-mentee relationship and the interactional dynamic might be different. Providing constructive feedbackAt the very start of my career, one of my collaborators said something that impacted me a lot. As the first author of our paper, she wrote the first draft. I then reviewed it and put down questions that I had for her writing. Later, when she was giving me feedback, she told me being a collaborator is more than raising questions and finding flaws. “What I wrote on the paper”, she said, “is undoubtedly the best of what I could think of at the moment. If you think there are limitations, could you please also provide potential solutions?” Until now, her words still stick with me and it’s something I live by. Indeed, good collaborators work together to identify problems and figure out solutions; if someone is only raising questions without following up on how to improve the paper, they would be more like a reviewer. From then on, whenever I am collaborating with someone and editing their work, I always make sure that I point out the imperfections, reasonings, and possible resolution to the problem, which could help us further discuss. As I understand how much effort it takes to edit and give doable advice to academic work, I make sure that I take pieces of advice seriously and respectfully. To be a good collaborator, we cannot be reluctant to consider others’ opinions and suggestions. If we only focus on our ideas and think that they are the best, there is no point in having collaborators. Establishing a clear division of laborEstablishing a clear division of labor is especially important in academia. Authors’ contribution to a paper and the authorship are crucial to building the scholarly identity and affect tenure and promotion. For example, one of my long-term collaborators and I have a very clear division of labor. The first author is usually responsible for analyzing data, writing the first draft of the paper, and leading revisions. If the analysis has to use multiple datasets or models and the second author is familiar with a certain dataset or model involved, the second author would be responsible for those parts of the analysis as well. If the literature in a certain part of the paper is in the field of the second author, the second author would write that too. Certainly, the idea for the paper, the conceptualization of the analysis, and the direction of the revisions often are the product of discussions between both authors. Every time before we start a new project, we would make sure to reach a consensus on who is going to be the lead author for the project, each person's responsibilities, and the general timeline. We would then update each other regularly on the research progress. We will try to have an agreement regarding when we could finish our parts and by what time we would send it over to the other person. In my opinion, to maintain a long-term collaboration relationship, we need to reach a consensus about how to allocate authorship fairly (i.e., in proportion to contribution). Reaching a well-balanced division of labor between collaborators requires communication and similar moral values. Showing respectA one-time experience of collaborating with a friend made me recognize the importance of respect in collaborations. When reading through her first draft, I upset her by sending her emails like text messages (without addressing her nor signing off my name). To make it worse, I did not send all of my opinions in one email, but I sent an email whenever I thought of something as I was looking through the draft. My collaborator later sent me an email confronting me and saying that what I did made her uncomfortable. We were collaborators, but not in an advisor-advisee relationship. The way I sent her emails and told her that we had to edit here and there put on an accusatory tone and made her feel disrespected. When I was reflecting on the matter, I recognized what I did was wrong. I apologized to my collaborator sincerely and explained that I didn’t mean to disrespect her. But I should have done a better job of communicating by reading through the whole work, organizing my thoughts, and sending her my feedback. She then told me that she chose to confront me because she wanted me to know and understand her feelings and she did not want this experience to harm our friendship. This incident has had a substantial impact on me. After this, whenever I work with people, I pay more attention to my manner: Is there an accusatory tone in my emails? Am I expressing appreciation for the work of my collaborators? Am I sending too many emails at once that would overwhelm people? These small details may also significantly affect the relationship between collaborators. Lifting each other upCheering for each other is so crucial. Once, a paper that my collaborator and I put together was desk rejected three times. As the first author, I doubted myself so badly. But my collaborator affirmed me and told me: "I think our article is very good, and it will be accepted." The assurance from my collaborator helped and encouraged me, and later, the article was indeed accepted by a good journal. Looking back, after three desk rejections, if my collaborator were to say "I don't like this article, and maybe we should give up," I might not be able to hold on and would’ve given up. In my opinion, lifting each other up between collaborators is more than encouraging each other after our project receives rejections. It also means that we have a positive evaluation of each other and feel optimistic about the research topic and progress. For example, many of my collaborators and I act as cheerleaders for each other. We would sincerely say: "This idea is great! We will put it together!" "Wow, you have edited it so well! The article is now so much better!" "Come on, we're almost done!" The research process is already long and winding. If collaborators are pessimistic, discouraging, or feeling hopeless about the research, the whole process may be overwhelmingly difficult. Cultivating long-term collaborationSome people may easily find new collaborators. Depending on the needs of a research project, it would be great if new collaborators with complementary expertise could always be found. But if you are fortunate enough to find a collaborator who is compatible with your intellectual capability, work style, research interest, and professional ethics, you must cherish it; if two of you can collaborate for a long time, it is one of the best things we could ask for.

Collaboration does not just happen. Some people say that you have to put in work to maintain an intimate relationship, and I think the same holds for collaborative partnerships too. My long-term collaborators and I will try to ensure that there are always ongoing and active projects. For instance, we will start the brainstorming process when a project is about to end, to see what we can do next. Sometimes we would even create an "idea bucket" which is filled with exciting new ideas for our future projects, and we discuss which one we should work on first. These are my sharing for now, and I welcome you to share your experience and thoughts. Author Note: Here is the link to the original article in Chinese: "找靠谱的合作者比找对象还难:How to collaborate?." The author, Yue Qian, would like to thank Ally Cheng for her assistance with translations from Chinese to English. Note: This article was first written in Chinese on February 6, 2016 and translated into English in 2021. I remember when I first entered grad school, I was talking to a mentor about research ideas. Whenever I brought up an idea, she would immediately recommend a relevant piece of literature for me to read. At one point, I was so impressed that I couldn't help but remark, “You’re like a walking encyclopedia! No matter what research topic I mention, you can always suggest a related article!” My mentor smiled and said, “Well that’s because I’ve been in academia for 20 years. When you reach this point of your academic career, there’s no doubt that you'll be even better than me.” Back then, I thought reaching a point like my mentor was far beyond me. But just a few months ago, I had two friends reach out to me to discuss their future research ideas, and they both said to me, "You're practically a walking encyclopedia. I could ask you anything, and you’d immediately recommend an article related to my idea." At that moment, I was reminded of myself when I just entered grad school and I realized that, since then, I had come a long way. Needless to say, I still have a long way to go compared to my mentor, but I am willing to allow myself more time to improve. So, if you feel like a layman right now, it is no big deal; we have all been there before. As long as you continue to grind toward your goal, you will eventually get there. Alright, let’s dive into today’s topic. I would like to share with you three things I have learned:

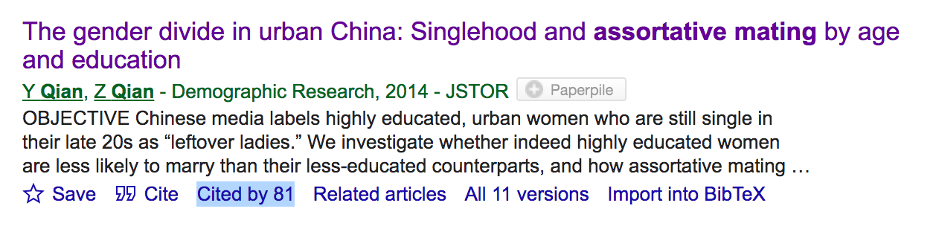

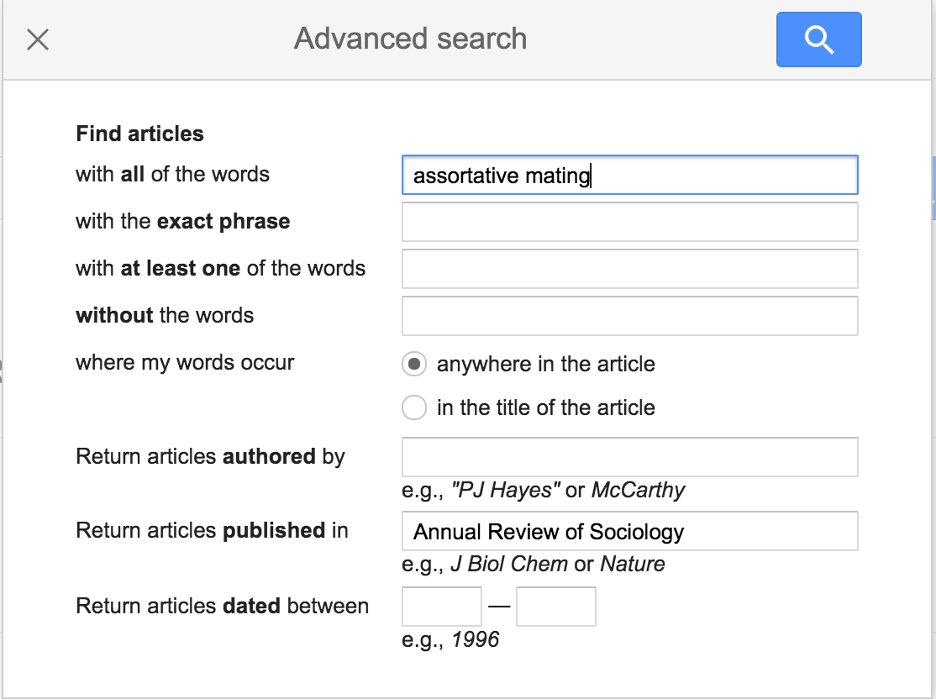

1. How does one become a “walking research database”? 1A. Read extensively. I am not sure about the sciences or humanities, but in social sciences, reading extensively is extremely important. My advisor once suggested that I should read the abstract of every new article from the best journals in our field (such as American Sociological Review, American Journal of Sociology, and Demography). Even if those papers do not belong to our particular area of research, it helps us get a sense of what people in the discipline are studying at the moment. So, how can you read extensively? 1B. Turn it into a habit, just like how you check Facebook, Newsfeed, or Twitter every day. My advantage is that I am very interested in my research field, so reading papers on marriage and family feels almost like reading a gossip magazine. For me, reading the abstract, or even the full text, does not feel like a chore in any way. To tell the truth, I find reading papers in English much more enjoyable than reading English novels. My advisor reads the New York Times every day to keep up with current events. Many New York Times articles will cite the latest literature, so if they are related to our research areas, we can also find the original journal articles to read. Several of the papers cited in my dissertation were mentioned in the New York Times articles that my advisor had forwarded to me. 1C. I am subscribed to various academic journals that interest me or are relevant to my research (use Journal of Marriage and Family as an example, "Get content alerts" as shown in the image below). Every time new articles are released, I receive an email notification. For general interest journals that are not closely related to my research areas, I scan the title of each paper and read it in full if I am interested. For journals that are directly related to my research areas (such as Journal of Marriage and Family), I will read the abstract of every article. The goal of this is to give my brain at least a vague impression of the research that is out there. If I ever need a particular piece of literature, that vague memory of the paper will resurface. I will then probably know which keywords to search for or which journals are more likely to have relevant literature. I also have many friends who follow and set up alerts for certain scholars or journal articles on Google Scholar. If those scholars publish a new article or if an article they follow is cited, they will automatically receive email notifications. If you've already published a paper, you can also set up a Google Scholar alert for it, and you will receive alerts about other published works that cite your paper. 2. If you have come up with a research question, how can you quickly find relevant literature? To answer that question, Google Scholar is a key resource. 2A. I typically search for relevant keywords in Google Scholar to find relevant articles. After I have read a relevant paper, I look at the references in that paper and read the associated literature. My mentor told me that this is called “searching backward.” That is, finding relevant literature as well as older or more classic literature. In addition, it is helpful to “search forward.” I will use my paper as an example (please excuse my lack of humility in doing so). On Google Scholar, each paper has a “cited by” in the lower left corner (see image below). If you click on “cited by,” you will see all of the new literature that has cited the work originally retrieved in your search. This way, you can get an idea of what progress has been made in academia since that paper was published. 2B. In sociology, we have a journal called Annual Review of Sociology. It's full of literature reviews written by experts on specific topics. I usually use the “Advanced search” function on Google Scholar to directly check whether this journal has published a literature review relevant to my research topic (see image below). If there is, I will most definitely read it, and then thoroughly look over its references. In addition, Journal of Marriage and Family, for example, will have a decade review every ten years. Typically, family scholars will read all of the papers in this issue (e.g., The Decade in Review published in 2020). If you're new to a research area, you can start by looking at review-type articles from some of the top journals to quickly locate relevant literature. 2C. Another method I often use is to find famous scholars in the field who have published relevant works to my research question. I then read their CV or Google Scholar profile to identify relevant papers that I should read. For several of my papers, my mentor advised me to check out so-and-so’s work because they were experts in that area of research.

2D. Another strategy is to use analogies. For example, when I write a paper on China, I will look at how the same research question is studied in the US context. What theories have been used? What methodology? In another example, I did a project on occupational segregation (update: this project led to a paper published in Social Science & Medicine), but I noticed that there was very little research on this topic. By comparison, there were a lot of studies on residential segregation in the US. Thus, I looked at those papers to see what theories the authors used to develop their hypotheses. I asked myself, “Can it be applied to occupational segregation?” (update: this exercise led me and my collaborator to write Section 2.1 of the paper "Segregation and Health: the missing links of occupation and immigrant status".) Of course, if there's not much literature on a research question, you have to ask yourself: is there something wrong with the question itself? To ensure the feasibility of your research question, it’s good to discuss with your advisor or more experienced researchers. 3. How can you read quickly and use relevant literature effectively? 3A. First of all, it is quite normal to take a long time reading papers when you are new to a research area. Be patient. You need to take time and settle in when you conduct research. As you become more familiar with a research area, you will start to read papers faster. For instance, all of the scholars studying a particular topic might apply the same theories. In this case, just give the basic introduction of the theory a quick skim, then skip it. In addition, the scholars may be using similar data, so just skim over the introduction of the data, and move on. Scholars of the same field may also use the same methods; if there is no innovation in terms of the method, then again, skim over it to find out what the method is, and move on. When you are reading your first introductory literature on a topic, you will most likely spend quite a bit of time reading it. As you become increasingly familiar with the body of literature, you can finish skimming a paper on that topic within a pretty short amount of time. 3B. You have to be clear about what your goal is when reading a paper. When I was writing my MA thesis, the topic I was studying had been examined in the US context, but my research was going to be focused on China. Thus, I read all of the papers that were examining the same issues in different societies (such as the US, Korea, and Spain). My purpose, in this case, was to see how the authors of these papers framed their unique contexts. In other words, what data they used didn’t matter to me, and every paper applied the same methodologies or major theories, so I simply skimmed these parts. With this method, it took me half an hour at most to read an article. When I was writing my dissertation, I also used this strategy. After deciding on the method I would use, I found the best journal in my research area and searched up that method as a keyword to find all the studies in the last 10 years that applied the method. I skipped through the theories they applied and their conclusions, because it was irrelevant for my research purposes. After briefly skimming through the introduction to get an idea of their research questions, I skipped straight to their method sections and then looked at how they explained the results. Moreover, in the process of doing so, I learned about new developments in this method (update: this chapter of dissertation using multilevel dyad models has been published in Journal of Marriage and Family), which were not mentioned in classical statistics textbooks. Therefore, instead of using the basic method, I ended up using an advanced version of it, inspired by an article I read (despite the article’s research question being unrelated to mine). This is also a good time for you to think about your audience. For example, when I write a paper, my goal essentially is to submit my paper to the journal where I search for literature, so I look for relevant literature from that journal. In general, when you read literature, make sure to keep your paper in mind. Always ask yourself: How can this previous literature serve my research? Similarly, there are certain papers where I only read the theory portion. For others, I only look at how they present the data they use. For some papers, I even choose to only read the introduction, because I want to know how scholars sell their research to quickly convince readers, “My research is really important!” If you are only reading the introduction part of a paper, the paper doesn’t necessarily need to be related to your research questions; the key is to read the papers that you like or are authored by your favorite scholars. Through reading these papers, you get to see how scholars frame and sell their research questions, which I think is an art in and of itself and requires conscious learning. There are a couple of scholars whom I really like, and I read every single one of their articles multiple times. As I read, I continuously take notice of how these scholars wrote and structured their articles. In other words, we should not simply take the literature for what it is—pages of words. Rather, we should read thoroughly. We should think while we are reading to really take it in. Only in this way can we benefit from our reading. Meanwhile, in each of your papers, there are always several key articles that are cited repeatedly. They provide you with either theories or methods that you need to draw on. Other times, it could be a conclusion that you want to challenge in your paper. In short, these key articles are either examples for you to learn from, or it's a target, in which case you would want to challenge it. I usually read these papers very, very thoroughly. Read carefully from start to finish. Print it out. Keep it handy when I am writing my paper. Doing these steps will make that article almost as familiar as my own paper. When my friends asked me a question related to an article I cited often, I could immediately tell them the details such as which table in the article had the result they wanted to know about. The strategies I have summarized above emerged through my own experience of reading journal articles. Hopefully it can be of help to you. If you have any good reading tips, you are also more than welcome to add on! Author Note: Here is the link to the original article in Chinese: "如何成为高效阅读的‘文献活字典’?." The author, Yue Qian, would like to thank Doris Li for her assistance with translations from Chinese to English. |

Yue QianAssociate Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|