|

Note: This article was first written in Chinese on February 6, 2016 and translated into English in 2021. I remember when I first entered grad school, I was talking to a mentor about research ideas. Whenever I brought up an idea, she would immediately recommend a relevant piece of literature for me to read. At one point, I was so impressed that I couldn't help but remark, “You’re like a walking encyclopedia! No matter what research topic I mention, you can always suggest a related article!” My mentor smiled and said, “Well that’s because I’ve been in academia for 20 years. When you reach this point of your academic career, there’s no doubt that you'll be even better than me.” Back then, I thought reaching a point like my mentor was far beyond me. But just a few months ago, I had two friends reach out to me to discuss their future research ideas, and they both said to me, "You're practically a walking encyclopedia. I could ask you anything, and you’d immediately recommend an article related to my idea." At that moment, I was reminded of myself when I just entered grad school and I realized that, since then, I had come a long way. Needless to say, I still have a long way to go compared to my mentor, but I am willing to allow myself more time to improve. So, if you feel like a layman right now, it is no big deal; we have all been there before. As long as you continue to grind toward your goal, you will eventually get there. Alright, let’s dive into today’s topic. I would like to share with you three things I have learned:

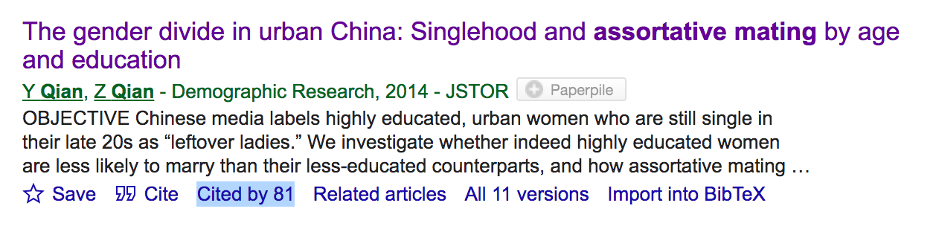

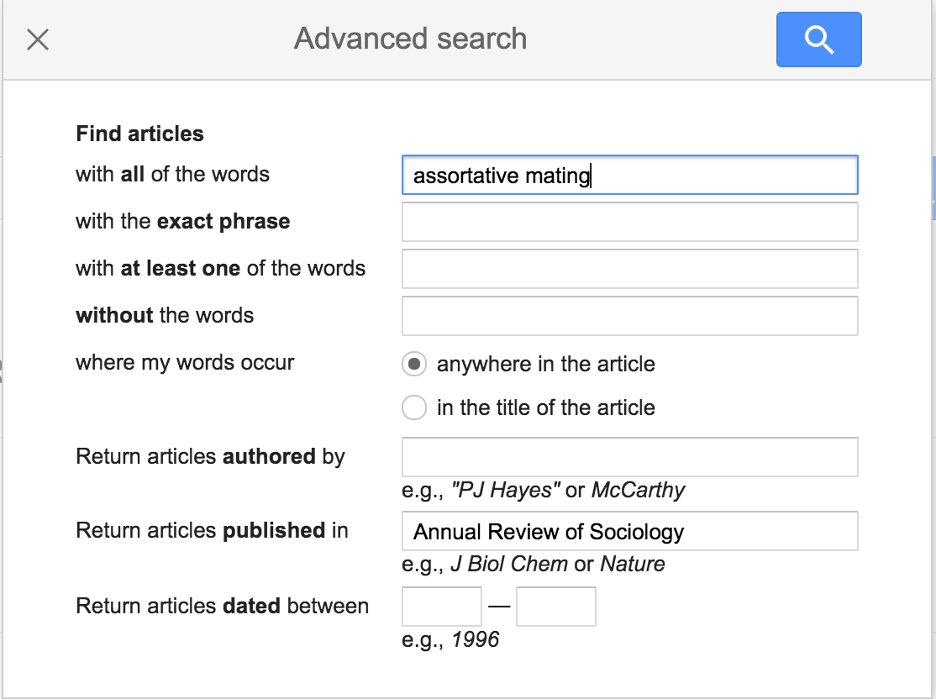

1. How does one become a “walking research database”? 1A. Read extensively. I am not sure about the sciences or humanities, but in social sciences, reading extensively is extremely important. My advisor once suggested that I should read the abstract of every new article from the best journals in our field (such as American Sociological Review, American Journal of Sociology, and Demography). Even if those papers do not belong to our particular area of research, it helps us get a sense of what people in the discipline are studying at the moment. So, how can you read extensively? 1B. Turn it into a habit, just like how you check Facebook, Newsfeed, or Twitter every day. My advantage is that I am very interested in my research field, so reading papers on marriage and family feels almost like reading a gossip magazine. For me, reading the abstract, or even the full text, does not feel like a chore in any way. To tell the truth, I find reading papers in English much more enjoyable than reading English novels. My advisor reads the New York Times every day to keep up with current events. Many New York Times articles will cite the latest literature, so if they are related to our research areas, we can also find the original journal articles to read. Several of the papers cited in my dissertation were mentioned in the New York Times articles that my advisor had forwarded to me. 1C. I am subscribed to various academic journals that interest me or are relevant to my research (use Journal of Marriage and Family as an example, "Get content alerts" as shown in the image below). Every time new articles are released, I receive an email notification. For general interest journals that are not closely related to my research areas, I scan the title of each paper and read it in full if I am interested. For journals that are directly related to my research areas (such as Journal of Marriage and Family), I will read the abstract of every article. The goal of this is to give my brain at least a vague impression of the research that is out there. If I ever need a particular piece of literature, that vague memory of the paper will resurface. I will then probably know which keywords to search for or which journals are more likely to have relevant literature. I also have many friends who follow and set up alerts for certain scholars or journal articles on Google Scholar. If those scholars publish a new article or if an article they follow is cited, they will automatically receive email notifications. If you've already published a paper, you can also set up a Google Scholar alert for it, and you will receive alerts about other published works that cite your paper. 2. If you have come up with a research question, how can you quickly find relevant literature? To answer that question, Google Scholar is a key resource. 2A. I typically search for relevant keywords in Google Scholar to find relevant articles. After I have read a relevant paper, I look at the references in that paper and read the associated literature. My mentor told me that this is called “searching backward.” That is, finding relevant literature as well as older or more classic literature. In addition, it is helpful to “search forward.” I will use my paper as an example (please excuse my lack of humility in doing so). On Google Scholar, each paper has a “cited by” in the lower left corner (see image below). If you click on “cited by,” you will see all of the new literature that has cited the work originally retrieved in your search. This way, you can get an idea of what progress has been made in academia since that paper was published. 2B. In sociology, we have a journal called Annual Review of Sociology. It's full of literature reviews written by experts on specific topics. I usually use the “Advanced search” function on Google Scholar to directly check whether this journal has published a literature review relevant to my research topic (see image below). If there is, I will most definitely read it, and then thoroughly look over its references. In addition, Journal of Marriage and Family, for example, will have a decade review every ten years. Typically, family scholars will read all of the papers in this issue (e.g., The Decade in Review published in 2020). If you're new to a research area, you can start by looking at review-type articles from some of the top journals to quickly locate relevant literature. 2C. Another method I often use is to find famous scholars in the field who have published relevant works to my research question. I then read their CV or Google Scholar profile to identify relevant papers that I should read. For several of my papers, my mentor advised me to check out so-and-so’s work because they were experts in that area of research.

2D. Another strategy is to use analogies. For example, when I write a paper on China, I will look at how the same research question is studied in the US context. What theories have been used? What methodology? In another example, I did a project on occupational segregation (update: this project led to a paper published in Social Science & Medicine), but I noticed that there was very little research on this topic. By comparison, there were a lot of studies on residential segregation in the US. Thus, I looked at those papers to see what theories the authors used to develop their hypotheses. I asked myself, “Can it be applied to occupational segregation?” (update: this exercise led me and my collaborator to write Section 2.1 of the paper "Segregation and Health: the missing links of occupation and immigrant status".) Of course, if there's not much literature on a research question, you have to ask yourself: is there something wrong with the question itself? To ensure the feasibility of your research question, it’s good to discuss with your advisor or more experienced researchers. 3. How can you read quickly and use relevant literature effectively? 3A. First of all, it is quite normal to take a long time reading papers when you are new to a research area. Be patient. You need to take time and settle in when you conduct research. As you become more familiar with a research area, you will start to read papers faster. For instance, all of the scholars studying a particular topic might apply the same theories. In this case, just give the basic introduction of the theory a quick skim, then skip it. In addition, the scholars may be using similar data, so just skim over the introduction of the data, and move on. Scholars of the same field may also use the same methods; if there is no innovation in terms of the method, then again, skim over it to find out what the method is, and move on. When you are reading your first introductory literature on a topic, you will most likely spend quite a bit of time reading it. As you become increasingly familiar with the body of literature, you can finish skimming a paper on that topic within a pretty short amount of time. 3B. You have to be clear about what your goal is when reading a paper. When I was writing my MA thesis, the topic I was studying had been examined in the US context, but my research was going to be focused on China. Thus, I read all of the papers that were examining the same issues in different societies (such as the US, Korea, and Spain). My purpose, in this case, was to see how the authors of these papers framed their unique contexts. In other words, what data they used didn’t matter to me, and every paper applied the same methodologies or major theories, so I simply skimmed these parts. With this method, it took me half an hour at most to read an article. When I was writing my dissertation, I also used this strategy. After deciding on the method I would use, I found the best journal in my research area and searched up that method as a keyword to find all the studies in the last 10 years that applied the method. I skipped through the theories they applied and their conclusions, because it was irrelevant for my research purposes. After briefly skimming through the introduction to get an idea of their research questions, I skipped straight to their method sections and then looked at how they explained the results. Moreover, in the process of doing so, I learned about new developments in this method (update: this chapter of dissertation using multilevel dyad models has been published in Journal of Marriage and Family), which were not mentioned in classical statistics textbooks. Therefore, instead of using the basic method, I ended up using an advanced version of it, inspired by an article I read (despite the article’s research question being unrelated to mine). This is also a good time for you to think about your audience. For example, when I write a paper, my goal essentially is to submit my paper to the journal where I search for literature, so I look for relevant literature from that journal. In general, when you read literature, make sure to keep your paper in mind. Always ask yourself: How can this previous literature serve my research? Similarly, there are certain papers where I only read the theory portion. For others, I only look at how they present the data they use. For some papers, I even choose to only read the introduction, because I want to know how scholars sell their research to quickly convince readers, “My research is really important!” If you are only reading the introduction part of a paper, the paper doesn’t necessarily need to be related to your research questions; the key is to read the papers that you like or are authored by your favorite scholars. Through reading these papers, you get to see how scholars frame and sell their research questions, which I think is an art in and of itself and requires conscious learning. There are a couple of scholars whom I really like, and I read every single one of their articles multiple times. As I read, I continuously take notice of how these scholars wrote and structured their articles. In other words, we should not simply take the literature for what it is—pages of words. Rather, we should read thoroughly. We should think while we are reading to really take it in. Only in this way can we benefit from our reading. Meanwhile, in each of your papers, there are always several key articles that are cited repeatedly. They provide you with either theories or methods that you need to draw on. Other times, it could be a conclusion that you want to challenge in your paper. In short, these key articles are either examples for you to learn from, or it's a target, in which case you would want to challenge it. I usually read these papers very, very thoroughly. Read carefully from start to finish. Print it out. Keep it handy when I am writing my paper. Doing these steps will make that article almost as familiar as my own paper. When my friends asked me a question related to an article I cited often, I could immediately tell them the details such as which table in the article had the result they wanted to know about. The strategies I have summarized above emerged through my own experience of reading journal articles. Hopefully it can be of help to you. If you have any good reading tips, you are also more than welcome to add on! Author Note: Here is the link to the original article in Chinese: "如何成为高效阅读的‘文献活字典’?." The author, Yue Qian, would like to thank Doris Li for her assistance with translations from Chinese to English.

0 Comments

Note: This article was first written in Chinese on April 26, 2019 and translated into English in 2021.

A 2018 study published in Nature Biotechnology found that the prevalence of moderate to severe depression and anxiety among graduate students was more than six times the prevalence among the general population. Nature’s 2017 PhD survey revealed that doctoral students were most concerned about things like work-life balance, future career prospects, and financial issues. These findings highlight the significant mental health challenges faced by academics. I used to struggle with taking care of my mental health. At the beginning of my graduate studies, I was worried that I couldn’t write a good MA thesis and I almost cried in front of my advisor. Later, I successfully defended my MA thesis, but I then started to doubt whether I could come up with a dissertation topic. Again, I discussed my “emotional panic” with my advisor. When it came time to graduate, worries over unemployment during my job hunt drove me to break down once more. I did end up finding a job, but there was immense stress in my first year of working. I had to move, prepare materials for my lessons, apply for a work visa, and adjust to an entirely new environment. On top of all this, I had no time to develop any new projects, and papers submitted for peer review had all been rejected. This brought me to another breaking point with my advisor, as I worried that, if this trajectory continued, I would not be able to get tenure. However, in my third year of working, my mentality had a drastic shift in a positive direction. I slowly started to accept that I was the type of person who gave their all to whatever they were working on. Even if a few years later I did not get tenure, I would be fine. I came to believe that, with my capabilities and work ethic, I could excel in other jobs even if academia did not work out. As I learned to prepare for the worst, hope for the best, and take whatever comes my way, I finally felt at ease to tackle anything the future had in store. Because I am easily troubled by my mental health issues, I try to be mindful of practical strategies that help improve my mental state. I have found some tips useful to me and I will share them in this article. I am hoping that, by sharing my experiences, I can start a discussion about how to take care of our mental health. If there are techniques that you have found helpful, please feel free to share them. Never compare yourself to others This is SO important. I have never been one to heavily compare myself to other people. In high school, I was in an “Olympic Class” in which students were trained for international science Olympiads and, for a long time, I scored in the bottom three of the class. Despite this, I studied at my own pace and was accepted into Renmin University of China, a prestigious university. Therefore, since high school, I have accepted that there are plenty of smarter people out there in the world. Rather than comparing myself to them, I should just focus on improving myself and doing what I need to do. In academia, smart impressive people abound. From big names to rising stars to job market stars, intelligent and remarkable people are everywhere. Furthermore, in academia, everything is public information. If you want to see who won an award, what paper someone has published, or what research funding people have secured, all it takes is a quick google search. Surrounded by brilliance and bombarded with updates of these individuals’ every move, we understandably feel anxious about our status and success. Fortunately, very rarely would I compare myself to others. When I began my PhD studies, I made very slow progress but I felt grounded with my pace. Although it was monotonous reading articles and writing papers all day and every day, doing these things calmed me down. Thinking back, in my six years of graduate studies, my mental health hit rock bottom when I began job hunting. I couldn’t help but browse the “Sociology Job Market Rumours” forum to keep tabs on who got campus interviews and who received job offers, which caused me to look at my situation with worry as I had not heard back from any of my applications. This addiction to constantly comparing my (lack of) progress to the achievements of others did not benefit me at all. Conversely, it triggered excessive anxiety, took up a lot of my time, and consumed my mental energy. Among my current colleagues, some publish a number of first-authored articles in top journals every year, some have received millions in national funding for their research projects, and still others have countless awards under their belt. Nonetheless, I do not compare myself to those who work alongside me or those in my field. Everyone’s career path is different and everyone’s road to success is unique. Differences in research areas, scholarly interests, methodological approaches, and target audiences all lead to variations in research output. There is no use in comparing our own path to another’s. Focus on the present In the beginning, I mentioned how I struggled with mental health. In reflection, my biggest weakness is that I have trouble staying calm and tend to focus on worst-case scenarios (in Psychology, it is known as “catastrophizing”). This kind of mindset makes me very prone to feelings of anxiety. For example, when I first began my job, I was already worrying about the future. Would I be able to get tenure in the next six or seven years? What would I do if I couldn’t? During my PhD years, when I shared my worries with my advisor, he was always very patient with me. He would calm me down and tell me that, “Don’t worry so much. Don’t worry about what will come in three or five years. Just focus on the next three months. Think about what goals you can work on right now and do your best to accomplish them. We have no control over the things that will happen three or five years from now.” It took me a long time to understand what my advisor taught me. Why do I emphasize focusing on the present? I have realized that, when I feel anxious and irritable, it is almost Zen to engage in self-calming exercises like analyzing data, writing papers, and editing papers. Doing these things allows me to momentarily forget all that is weighing on my mind and grounds me in a feeling of pure happiness. Rather than worrying about things that will happen half a decade from now, I like to try and appreciate the process of doing things I love. This is my understanding of how focusing on the present can help relieve moment-to-moment stress. Focusing on the present moment can also help manage stress in the long term. When I was developing my dissertation proposal, I could only come up with the topics for two empirical chapters out of the three required. My advisor said to me, “It’s alright, just start writing. When you analyze data and write your first two chapters, a third topic will naturally come to mind.” Later, when I began my job, I confessed to my advisor that I was not sure what my next big project should be. He said, “you are not a book scholar, so you don’t need to worry too much about what your next big project will be. Just think about what topic you would like to explore in your next paper. In the process of writing it, inspiration for your next project will come naturally.” Things played out exactly as my advisor had said. My third dissertation chapter was finished with ease. My project ideas came flowing one after another and I tackled each project one step a time without feeling drained of ideas. Let me give an example. I was once invited by a colleague to contribute a paper to a journal’s special issue. I readily agreed because at the time my collaborator and I were just about to write a paper that precisely fit the theme of the special issue. When we were writing the article for the special issue, I found another point of interest for further research. As such, my collaborator and I wrote another article that is now under review for publication. Moreover, through contributing to this special issue, I connected with an early-career scholar whose work I had been following. We agreed that once we wrapped up our articles for the special issue, we should collaborate. The resulting collaborative article that came from our informal conversation has now been accepted for publication. [Update: the three papers were about women's fertility autonomy in China, premarital pregnancy in China, and assortative mating in remarriage in China, respectively. All three papers have been published by now.] The experiences I have had these past few years allow me to slowly understand that the best ways to deal with my anxiety are to be present in the moment and to enjoy the feelings of fulfillment brought about by “mindful working.” I earnestly work on every paper and challenge myself to think of new areas of research in the process. As I give my all to the current opportunities within my control, I worry less about what will happen in the future. Find something that keeps you going I feel that it is very easy for people in academia to question the meaning of their work. It is also easy to feel frustrated and fall victim to self-doubt. One reason is that every project takes several years to be fully completed (it takes an even longer time if people are looking to publish a book). Additionally, when papers go under review, they can be criticized harshly and rejected in an instant, turning the hard work that went into it to dust. At times like these, it is difficult to not question oneself. Thus, I believe it is very important to find meaningful things to engage in. For me, that has been public sociology. I am very passionate about disseminating social sciences research to the general public (particularly when it comes to topics of marriage, family, and gender). The reach of most academic papers is very limited, so many important findings are not noticed by the average individual. I find that it is an extremely gratifying experience to convey scholarly findings in digestible terms to those beyond the academic sphere. Writing articles for popular media while staying true to science has become a creative hobby of mine. Over the course of writing, I have discovered that this creative outlet has significantly relieved me from work stress. Some of my friends love to teach. They enjoy helping their students grow and that is a source of fulfillment for them. Another friend of mine specializes in research on gender and work. She served as a consultant for many local organizations in hopes of promoting workplace diversity and inclusion. Find something that keeps you going, instead of focusing all your meaning-making on publishing academic papers. This is something I find helpful for maintaining good mental health in academia. Having a guilty pleasure This tip was inspired by a friend. To put it simply, we need to find our favorite way to spend our leisure time. For a long time, my guilty pleasure was keeping up with new episodes of Gossip Girl every week or watching various music videos from my favorite singer Jane Zhang. Later, I followed a Chinese reality show about intimate relationships, which featured the interactions of three celebrity couples. I was really engaged with the TV series and entertainment shows I liked. For example:

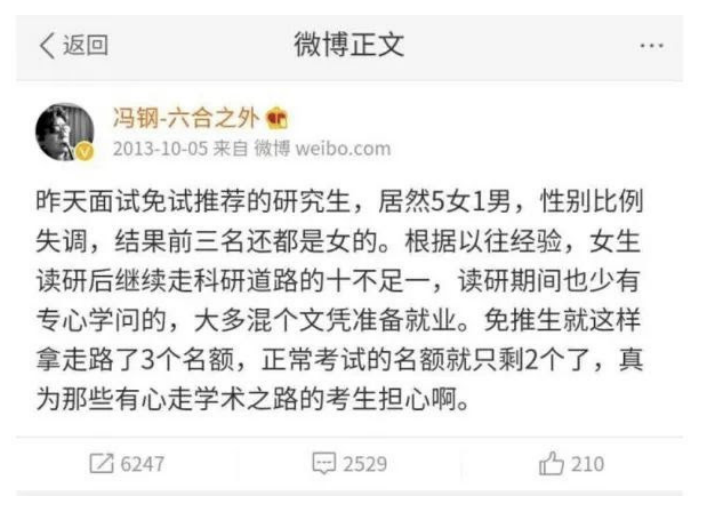

Every week, when I was waiting to watch new episodes of TV shows, it became something that I could look forward to. Moreover, when I was watching those shows, I forgot all about work-related stress. In conclusion, I highly recommend everyone find their guilty pleasure, immerse yourself deeply (do it in moderation, however), and enjoy yourself. This is also another way to maintain positive mental health. Of course, the aforementioned examples are all drawn from my personal experiences. Please feel free to share any well-kept secrets of your guilty pleasures or helpful strategies. Author Note: Here is the link to the original article in Chinese: "如何在学术界保持心理健康?." The author, Yue Qian, would like to thank Evalina Liu for her assistance with translations from Chinese to English. Note: This article was first written in Chinese on October 24, 2017 and translated into English in 2018. A post written on Weibo (a Chinese microblogging website) in 2013 by Feng Gang, a sociology professor from Zhejiang University, has recently resurfaced and led to a heated discussion online. My friend and colleague suggested that as a leading blog in China that aims at promoting gender equality, Ms-Muses should publish a response. Therefore, I take the initiative to write this article. I would like to start by sharing my experience growing up from a little girl (in a patriarchal society) to a university professor (with research interests in gender relations and social inequality). I will also provide some relevant research findings later in this article.

Ever since I was little, my mom, along with my friends’ parents, had always told us, “Women should not work too hard. It is far more important for girls to marry well than anything else.” Yet, under such childhood environments, I became a feminist.

Although I was always at the top of my class from elementary school to junior high school, all my teachers, even my mom included, kept reminding me that getting good grades in my early education did not necessarily mean that I would still get good grades later on. In contrast, although my male classmates were not as hardworking, and their grades certainly were not as good, they still often received praises from teachers and parents saying, “You are so smart; you will have really good grades if you just put in a little bit more effort.” To this day, I still remember one math teacher in my elementary school, who had a respectable reputation in the district, commented in my homework: “Yue’s academic performance is good, but she is not smart. She’ll have to work hard to make up for a lack of intelligence.” In high school, I got into the “Olympic Class” in which students were trained for international science Olympiads. We had to learn three years’ worth of math, physics, biology, and chemistry in Grade 10. I had a hard time catching up to this kind of pace and my grades began to drop, which seemingly confirmed the conventional expectation that “girls would eventually fall behind boys in school.” My math teacher even arranged a one-to-one meeting with me, suggesting that I should drop out of the “Olympic Class.” Looking back, I am actually very proud of my younger self. Despite being a powerless little girl, I was brave and determined enough to tell the powerful male teacher, “No, I am not quitting. I want to stay.” (To some degree, I also feel grateful that he respected my decision at that time.) In order to stay in the class, I worked extra hard throughout the rest of my high school years. I wrote down every question that teachers discussed in class, and then went over it again on my own. The next day, I asked my friends to explain to me the harder questions that I did not understand. I scored only 46% in math exams for a long time, but in my last year of high school, my mark went up to 92% for the first time. At the time I felt very satisfied with my progress. However, my math teacher said to me privately, “You did well this time…(pause)…but it was mainly because the exam was easier”. In fact, up until the end of high school, I maintained my math average at 92%. How can I still vividly remember things that happened over ten years ago? It is because these kinds of encounters have made me realize how bumpy and difficult the road to success can be for women. In addition, in every mock exam, nine out of the top ten students in my cohort were female. Yet, our Chinese teacher made a comment in front of the whole class, “There is only one male student out of all top ten students in sciences; this is very abnormal. In an older cohort, there was only one female student among the top ten students; that’s the way it should be.” Even as a high school student, I already wanted to start a revolution in class. Why was it considered as “abnormal” for female students to achieve academic excellence? Why was my performance in math attributed only to hard work, but not to my intellectual ability? Why did the teacher think it was only because “the exam was easier” when my math grades significantly improved? Looking back, my reactions were quite immature at the time. I used my rebellious adolescent way to show my resentment. For example, I would sleep through my Chinese class, eat my breakfast during early morning classes, and remain seated while my teacher demanded me to stand still for a certain period of time. During my senior year of high school, I remained among the top students in my cohort. Eventually, I went on to a prestigious university in Beijing. Strikingly, I encountered a male professor in college who expressed his belief in class that “women do not belong in academia.” I found it extremely ridiculous that he could make such remark when he had so many outstanding female colleagues and had a daughter as well. In graduate school, there were many incidents where my friends, who worked in male-dominated fields, told me that “male graduate students in the department always get together and gossip about the female professors who all seem to be beautiful blonde women.” All these experiences sparked my interest in gender studies. From undergrad, to grad school, and PhD, I met numerous inspiring and accomplished female role models whom I looked up to. Their hard work, rigorous research, and passionate curiosity, along with their genuine desire to provide support and guidance for students, aspired me to push forward. As I got to know more about gender research, I realized that girls have been outperforming boys for a long time in the classroom. According to U.S. historical evidence, girls had long surpassed boys academically in secondary school. One reason why women lagged behind men in attaining tertiary education was that most universities did not accept female students (DiPrete & Buchmann 2013). It was not until the inception of the Seven Sisters (colleges) that most universities began accepting female applicants. Currently, in the United States, about 60% of the bachelor’s and master’s degrees and 50% of the doctoral degrees are awarded to women. Even in China, women have surpassed men in college enrollment ever since 2009 (Yeung 2013). Nevertheless, even today, we still see comments such as “less than 10% of female graduate students take academia as their career path after graduation.” Professor Feng Gang should ask himself: Is it really because women are less competent? How come we never question whether the academia is really female-friendly? Women still take on a greater share of the housework and childcare burden. Balancing familial and domestic duties with work is something that most female PhDs and professors have to consider and worry about. Claudia Goldin (2004) found that by their mid-30s to mid-40s, college graduate men managed to achieve career and family about two times as often as women. A lot of times, women are put into the predicament to choose between their career and family, but this is seldom a problem that men have to face. Even if women work harder to balance both work and family, they may still be unfairly evaluated as less ideal workers who will eventually drop out of the workforce for familial duties. Shelley J. Correll and her colleagues (2007) conducted an audit study in which participants evaluated application materials for a pair of equally qualified female job candidates who differed on parental status. The results showed that mothers were perceived as less competent and less committed to their work and were even recommended for a lower starting salary. This is my story. I believe every woman has their own story to share, a story that “nevertheless, she persisted.” Hillary Clinton once said, “Although we weren’t able to shatter that highest, hardest glass ceiling this time, thanks to you, it’s got about 18 million cracks in it and the light is shining through like never before, filling us all with the hope and the sure knowledge that the path will be a little easier next time.” It is numerous women’s effort and persistence that enable positive change, inspire action, and move communities forward. In short, every country should advocate for feminism and gender equality, not because women are men’s mothers, wives or daughters, but because “women’s rights are human rights.” The opportunities, successes, and accomplishments that women enjoy today are attributable to the perseverance and hard work of many generations of women. Throughout their lives, every woman faces gender discrimination both blatantly and covertly. Here, I would like to pay my tribute to all the women who have persisted, regardless of how many times the society has made them doubt themselves. I also want to ask everyone to stop judging girls and women based on stereotypes, because bias is what holds many women back. Author Note: Here is the link to the original article in Chinese: "一位‘坚持走科研道路’女学者的自白." The author, Yue Qian, would like to thank Christine Yang for her assistance with translations from Chinese to English. Note: This article was first written in Chinese on April 19, 2017 and translated into English in 2021.

After graduating in the US with a sociology PhD, I became an Assistant Professor at the University of British Columbia (UBC). This is a tenure-track position, meaning that the institution will appoint us for a few years followed by a performance evaluation. If we pass, we are granted tenure. If we fail the evaluation, we would have to pack our bags and leave. It has been nearly ten months since I started my position in July 2016. Reflecting on my first year of being a pre-tenure faculty member, I have gained some insight that I would like to share. Time management During my first year, I needed to teach three new courses. Therefore, I spent a great deal of time doing course prep. Given my previous training, I was more familiar with academic research on China and the US. Now that I am working in Canada, I hope to also teach my students about research on Canadian families. Hence, I spent a lot of time familiarizing myself with the current state of Canadian family research. Evaluations of teaching only make up a relatively small fraction of our tenure promotion evaluations. Even so, in my view, teaching involves direct interactions with students that can have significant impacts. If we are not well-prepared, there is almost immediate—and oftentimes face-to-face—negative feedback from students, which can take a huge toll on our emotions and self-esteem. Plus, I enjoy sharing my knowledge, so I consider it an intrinsic reward to inspire students through the research I like. In my teaching, I also encounter many eager and thoughtful students with high levels of critical thinking, and it is always a delight to exchange ideas with them. Our department head was very supportive of my research and accommodating of my work habits. In my second semester at UBC, I needed to teach two courses. The department had originally scheduled me to teach for 1.5 hours every day from Monday to Thursday. When I found out my schedule, I immediately wrote an email to the department head expressing some concerns I had. I typically need large chunks of uninterrupted time to conduct research, but teaching from Monday to Thursday would lead to a fragmentation of my time and thus a reduction of my research productivity. Subsequently, with the support of the department head, the staff responsible for scheduling helped me arrange my courses to be on Tuesdays and Thursdays only. Before I graduated with my PhD, my advisor urged me that I should allocate at least two days a week to research while on tenure track. For this reason, my basic work schedule involved teaching and addressing other related tasks on Tuesdays and Thursdays while concentrating on research on Mondays and Wednesdays. I usually worked on my research in my study room at home instead of going to my office. This helped to reduce my commuting time, avoid other external distractions, and establish my spatialized rituals (as recommended by Helen Sword in her book Air & Light & Time & Space: How Successful Academics Write). I usually spent Fridays doing course prep whereas, on weekends, I tried my best to get some rest. Although the plan sounded well-structured, my Mondays and Wednesdays intended for research were frequently interrupted by other matters, so in reality, I had less time for research than planned. In my personal experience, if I do not block out time for my research, I will easily be carried away by other matters, but everyone works differently. For example, I have colleagues who wake up at 5 AM every day, work until noon, and spend the afternoon taking care of other tasks. The key is to figure out what strategies work best for you and to stick to them. Undoubtedly, there is a lot of pressure for pre-tenure faculty members. If we want to keep a sustainable lifestyle and remain highly engaged with research in the long run, we have to find a work-life balance. Otherwise, we will easily experience physical and mental burnout. When I was a grad student, I tried all kinds of stress management techniques: online shopping, exercising, playing the piano, binge eating, and drinking, to name a few. Some were healthy coping strategies, while others, not so much. After I came to Vancouver, I actually had little desire to shop or binge eat; I drank but only moderately. What is my new stress reliever? At the end of every workday, whether I was teaching or doing research, I would inevitably feel exhausted, hollow, and ‘brain-dead.’ To counter this, I have started practicing hot yoga regularly, which always makes me feel rejuvenated after every session. I try to do one hour of hot yoga four to five times a week. I chose this exercise partly because I have always liked doing yoga, but mostly because a yoga studio is five minutes’ walk from my apartment. The convenient distance and the fact that I have already paid for monthly membership give me no reason to slack off. My hour-long yoga sessions are really a time when I can take my mind off other things. I also have friends who run, weightlift, or play tennis. The key to staying healthy is to overcome our inertia and get a fitness routine off the ground. Challenges at work I do not think I look particularly young among Asian appearances, but regardless, I am still relatively young as I went straight from undergrad to grad school and then to my current job. At the same time, I am an Asian immigrant woman. These demographic characteristics of mine make my work a bit challenging. What bothers me most are the challenges of teaching. In one of the courses I taught, I had a five-minute quiz at the beginning of each class time to make sure students had read the assigned articles. I soon realized that out of the 75 students in my class, many (there always appeared to be 5–10 per class time) left either after handing in the quiz or in the middle of the class. These students did so without seeking my permission or even informing me. It also happened that the classroom door was in the front of the room, so every time they left during class, it was very disruptive to me and to other students listening to the lecture. Although roughly only a tenth of the class did so, their detriment to my mood and self-esteem outweighed the positive impact of the majority of the students who were well-behaved and engaged. I was very troubled at the time, so I communicated with my colleagues to seek their advice. My colleagues validated my experience that, as a young female instructor, classroom management did sometimes pose a challenge. It was disheartening that sociology students, who learned about social inequalities in class, would perpetuate these “inequalities” based on age and gender (and, to some extent, race and immigrant status) in their daily interactions. I also spoke with a female colleague in the department who is an excellent instructor. She said she faced some of these challenges when she was younger, but one of the advantages of aging was that it became relatively easier to gain respect from students. Although compared to her male colleagues, she has more of mom-like authority than professor-like authority, being older makes it easier for her to manage her students. As I later reflected, Max Weber proposed three kinds of authority: traditional, charismatic, and rational-legal. If traditional authority was harder for a young immigrant minority woman to attain, I needed to establish rational-legal authority. For example, I will include “arrive no more than five minutes late and no early departures” in my syllabus next year. In addition, when I teach in the future, I plan to do pop quizzes—sometimes at the beginning of the class, sometimes at the end. In this way, I can check not only whether students have done the readings in advance but also whether they have paid attention in class. Hopefully, I can rely on established rules and expectations to promote positive student behavior and create a better classroom atmosphere. Social support As I transitioned from grad school to work, one of the biggest changes I have noticed is that suddenly there is no one else at the same stage as me. Demographers have always placed great emphasis on the concept of “cohort,” meaning that there are some commonalities among people who experience the same event at the same time. During grad school, there are usually five to ten students admitted in the same cohort. When we had to write a paper, prepare for PhD candidacy exams, or look for jobs, there was always someone to exchange ideas with and we could encourage one another. After we graduated and start working as faculty members, almost all of our colleagues are in different life stages and at various points of their careers. Everyone’s life and work priorities also differ. All of these make it difficult for pre-tenure faculty members to find a companion to forge ahead with. If there are any regrets from my first year of work, it would probably be the fact that I did not take the initiative to greet others or make friends since it takes time for me to get comfortable around others. As a result, I had hardly talked with several of my colleagues despite having worked in the department for nearly a year. Before I started working, my mentors shared their experience with me and advised me to take the initiative and try inviting every colleague out for coffee or lunch to increase my visibility in the department. However, such advice is difficult for introverts like myself to follow. Still, I do communicate frequently with my colleagues who are near my office. I have never been one to be afraid of asking questions. If I had a teaching or administrative question, I would immediately communicate with the department head, my assigned faculty mentor, or my colleagues in the adjacent office. Don’t forget about your past social support system! When I had questions or felt confused, I still sent emails to my mentors from grad school. They always replied to my lengthy emails with patience and helped me through many difficulties. In addition, I keep in touch with my former friends, especially those who have just started their tenure-track job. Although we live far apart, we are at similar stages of our careers, facing similar pressures and worries. Now, I am sharing my experiences in the hopes that you can feel the social support of the larger academic community. Research progress In my first year at UBC, I spent a considerable amount of time and energy doing course prep, teaching, and managing the classroom. On top of that, I moved across the border, was adapting to the new environment, and had to deal with all kinds of administrative procedures and immigration paperwork. Because of all these things, I did not publish any new articles. My takeaway is that it is a major challenge to start any new projects in the very first year of the tenure track. After starting my job, I submitted a paper and received a “revise and resubmit” request. Following a long period of revision, it was finally accepted. All of my papers that are currently under review and the ones that I am currently writing were initiated during my grad school days. They were “work-in-progresses” from back then, and now I am just starting to wrap up these projects. I feel that the “research pipeline” often mentioned by my mentors is quite important. It is crucial to plan well in advance and decide which papers need to be published before we are on the job market as well as which papers we need to write, submit, and get published as soon as possible while on tenure track. The peer-review cycles and processes are out of our control, so the only thing we can do is to keep writing and submitting, and to submit again if our paper is rejected. Besides, I think writing a sole-authored paper is an extremely lonely endeavor. In a sole-authored project, I will be the only person who knows the research thoroughly. Thus, it is difficult to discuss with others when I come across problems during the research process. Without a collaborator to keep me accountable, I often lack the motivation or the self-discipline to continue my work. For example, one of my sole-authored papers was rejected, and it has been almost half a year now, but I have yet to start revising it. So in reality, “keep writing and submitting, and submit again when rejected” is easier said than done. It is even harder to put into practice when it comes to working on a sole-authored paper. All things considered, I am fortunate to have many reliable and compatible collaborators whose research interests overlap with and complement mine. At the same time, they also are my friends and form my social support network. I have collaborated with them to publish various papers. After receiving my PhD, I have collaborated less with my advisors. Now, my primary collaborators are almost all friends of mine who, like me, are in the early stages of their careers (or towards the end of completing their PhD). We are all similar in terms of our work habits and work pace, and we share the same pressures of earning tenure. Moreover, everyone’s moral sense is very similar, so there are not any disputes or estrangements stemming from the division of labor or authorship. We should cherish collaborators who are compatible with our work abilities, research interests, and professional ethics. They are my collaborators but above all, valuable friends. Of course, the issue of how many articles you should work on alone and how many to collaborate on with others also needs to be adjusted and planned according to your institution’s standards and expectations for tenure and promotion. If you are at a university that discourages collaboration and places a lot of emphasis on sole-authored work, you will have to stick it out and do your own research no matter what. This is what I have learned so far. Inevitably, personal experience has its limits. For example, since I started my job, I have had less contact with my family and friends (especially those in China). Oftentimes when I called them, I tended to rush through the call. I am aware of this fact and feel very guilty towards them. However, as a single and childless person, I still have more time and freedom at my disposal. By contrast, assistant professors who are parents face the pressure of earning tenure on one end and the struggles of parenting on the other. They cannot control when their children cry or how their children behave, so they face different challenges in balancing work and life than I do. That being said, it would be such an honor if anything I have shared resonates with you. Author Note: Here is the link to the original article in Chinese: "在加拿大当助理教授的第一年:如何管理时间、情绪和研究进度?." The author, Yue Qian, would like to thank Doris Li for her assistance with translations from Chinese to English. |

Yue QianAssociate Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|